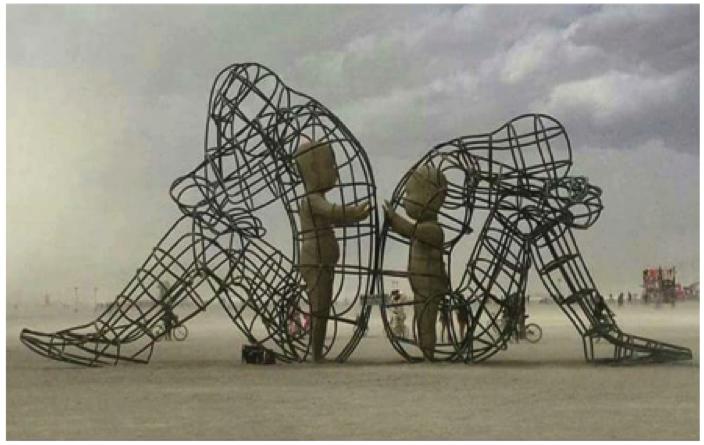

Burning Man Sculpture “Love”, by Alexandr Milov, Odessa, Ukraine

The previous meetings of the Discussion Group for Children of Holocaust Survivors addressed some of the problematic long-term effects of extreme trauma on the survivor parents, and the impact that such persistent post-traumatic reactions might have had on the family atmosphere and on survivors’ relationships with their children. We have also examined some of the inter-generational effects of having grown up with trauma survivor parents, and how particular characteristics of the relationships with the parents might influence the later relationships of adult children of survivors with their significant others and with their own children. The sixth meeting began to address what the children of survivors, now in their middle age, can do at this point to improve and deepen their intimate relationships with spouses and others. The meeting focused on the concept of becoming conscious and aware of the ways in which our relationships in the present are influenced by the legacy of the Holocaust and the ways we learned to love.

The premise presented, which will continue to be developed in the next meeting, was that our couple relationships provide us with a “second chance” at completing the unfinished business of our childhood. It is a second chance at re-visiting our childhood ‘wounds,’ with the purpose of healing them and becoming the full mature adult that we can become in the present, unhindered by old, automatic ways of relating to our loved ones. Old adaptations that we have used in the past in order to protect ourselves from pain become rigid and confining, and interfere with the deep wish to connect with the other. This idea is beautifully visually expressed by the artist Alexander Milov in his project “Love” exhibited in Burning Man.

“Conscious relationships” involve becoming aware of one’s automatic reactions to triggers in current interpersonal situations because of old patterns learned and internalized in earlier relationships with the family of origin. Frustrated needs and the defenses we developed to deal with such experiences are showing up every day in our relationships with loved ones.

A conscious relationship is one in which we do not respond automatically, unthinking, with defensive responses that are rooted in old habits and old wounds. Rather, in a conscious relationship we strive to become conscious of our “hot buttons,” the issues that trigger old hurts, old defenses. We intentionally focus on identifying these old patterns, trying to understand what are the things we are particularly and habitually offended by, and why we developed particular ways of responding to such a perceived slight. We intentionally focus on trying to understand what we learned about relationships in childhood. It is the family context where we all learn how to be with others, what does it feel like to be in a relationship, what about us seems loveable, and what about us seems not at all welcome in the relationship. As we grow up in a family we learn what then become our implicit ideas about relationships; we learn what has worked and what has not worked for us in the particular context of the particular parents and family we grew up in. Those parts of us that were received with joy, with approval, with appreciation, have become aspects of ourselves which we like and of which we are proud. Aspects of our selves that were frowned upon, criticized, mocked or just ignored, will have been neglected by us, and remain under-developed, or might even have become hated aspects of our sense of self. Confronted with situations in later relationships, when these aspects are called upon, pointed at, or summoned by our partner in various ways, we might respond defensively or aggressively, in the effort to avoid pain and hurt associated with these parts of our selves. As adults who wish to achieve a greater degree of freedom from old frustrations and wounds and to establish a deeper connection with others, we now must take responsibility for the repair by becoming conscious of our wounds and our defenses, conscious of our impact on our loved ones, and focused on the improvement of the relationships that matter to us, rather than on protecting ourselves from old and feared disappointments and hurts.

In a conscious relationship, we try to become aware of the particular contents of the learning about relationships that we acquired in our families of origin, and we try to intentionally re-assess whether our current perceptions, when we feel injured by a loved one, are based in current reality or in hyper-sensitivities that we “import” from the past. In conscious relationships we try to understand, as the adults we are today, why we developed certain adaptations, certain response styles, why they were useful in the particular context of our families while growing up, and how they served to protect us.

Some of us had to protect themselves from feeling too needy, because their parents were too over-burdened with their own difficulties to be available to offer support. Others had to learn how to protect themselves from the painful experience of parents who were over-anxious and over-reactive, easily triggered and over emotional, or on the contrary, emotionally detached and unable to respond sufficiently to the emotional needs of their children. We must understand what purposes our defenses served in order to be able to focus on what needs to change, what is no longer serving us well in the current reality of our relationships. In conscious relationships, we try to take responsibility for these old patterns that we bring with us, and for the negative impact of our responses on our partner or children. We try to intentionally re-evaluate how we would like to respond, rather than how we respond automatically.

Our goal in a conscious relationship is to re-connect or deepen our connection with our loved ones. We all wish to be deeply known, to feel that our true essence is seen, that our strengths are appreciated, and that our wounds are compassionately understood. In order to achieve this intimate relational mutual knowing we must develop constructive communication skills. We must learn to listen with an open mind, to be fully present and able to hear the other’s story from their own perspective. We must learn to truly make room inside ourselves to hear the other’s experiences along the journey that created who they are today, and why they might do the maddening, irrational things that repeatedly upset us and occasionally push us away from them and them from us. The purpose of exploring this developmental journey is to understand our own, and our spouse’s, “wounding” and especially to help develop a non-blaming, non-shaming way of understanding our self, our partner and our parents. Ultimately, our aim is to understand the unfulfilled childhood needs that are brought to the relationship in order to have a “second chance” at healing, so a mutual meeting of these needs can be facilitated, and self-hatred associated with such unmet needs can be dealt with.

The quality of parenting experienced by any given child ranges from more optimal to less optimal depending on the personality of the parents, the personality of the particular child, and many subjective and objective factors. Even children within the same family may experience differences in the quality of parenting, and each child may feel that their needs were met to a greater or lesser degree. Throughout childhood and adolescence, children go through developmental phases and have unique developmental needs that need to be met sufficiently well in order to achieve healthy functioning in all spheres.

My supervisor and mentor at Yale University, Dr. Sidney Blatt, articulated in his “Double Helix” theory that personality develops along two intertwined pathways, one focused on the development of a sense of identity, and another focused on relationships. Each stage in development has a particular set of demands and tasks that need to be accomplished, with some stages more focused on identity needs, such as the establishment of autonomy and competence, and others more on interpersonal relationships. Development in every stage builds on the accomplishments of the previous stage. Disruptions in either pathway, or an over-emphasis on either, can lead to different personality styles, different types of problems, and even different psychological symptoms. Problems around identity tend to be associated with a sense of “I am a failure,” while problems in the relatedness arena are associated with a sense of “I am unlovable.” Various developmental needs are experienced by children as having been met more optimally, or less optimally, in their families.

Attachment and relatedness needs are about the importance of bonding with others. Attachment needs are nurtured in the infant and child when the caretaker is reliably available, warm in contact, and empathically attuned to the infant’s needs. The message that is transmitted to the child when attachment needs are reasonably well-met is that it is OK to be, the world is safe, and needs will be met. The healthy outcome of satisfactorily met attachment needs is emotional security and a sense of self-coherence, a feeling that our various parts and aspects are well-integrated and accepted by others as well as by our self. These experiences provide us with a secure base from which to face the world, and with the capacity to adapt flexibly to changing environmental demands and to stress. When parents are survivors of trauma, in particular trauma inflicted by the viciousness of others, and when they have suffered terrible losses, they might implicitly and explicitly have difficulties communicating to their child that the world is safe. If parents continue to suffer from persistent post-traumatic reactions, including elevated anxiety, depressive experiences, or intrusive traumatic memories that are triggered by unexpected reminders of their trauma, they might not be reliably emotionally available to the child. They might appear impatient, inattentive, or critical of the child’s normative behaviors, of the child’s loudness, activity level, sensitivity, autonomy, or of other features. As a result, the child might experience himself or herself as too demanding, as being “too much” for the parent (or later, for others). The child might be particularly sensitive in later relationships to feeling, yet again, not sufficiently or not adequately responded to.

Another group of needs during the development of the self has to do with exploration, the need to venture out and explore the world around us, to separate and re-connect upon returning to our secure base. The developmental impetus, shown so clearly in the behavior of children who have just learned to walk and are exploring their newly acquired mobility, is to separate and re-connect. These needs are nurtured when the parent supports the child in venturing out, while at the same time setting reasonable limits, and when the parent is reliably available and warm upon re-connecting. When all goes well in the arena of the child’s, and the adolescent’s, exploration needs, the message they perceive is that it is okay to explore, and that it is okay to separate and return. The healthy outcome is that the child will begin to have a sense of separateness and safety within the context of a connection, and will retain their sense of curiosity. However, for trauma survivor parents it was sometimes difficult to trust that their child can separate and remain safe, that nothing terrible will happen to them if they leave the parents’ orbit. Trauma survivors have experienced traumatic and multiple losses, and separations, even minor separations, might be experienced by them with a poignancy that is disproportionate to the current reality, yet has often powerfully colored their responses to their children’s attempts to venture out into the world. As a result, children of survivors might have given up on their wishes to go away to college, for example, or to take a job that would separate them from their parents. Moreover, children who have internalized the sense that exploring and expanding into the world is either dangerous, or that it causes their parents pain, might come to (non-consciously) fear taking any kind of action that requires or implies separating and doing their own thing. Hence, for example, such “strange” adaptations seen later in some children of survivors, as the capacity to put one’s talents and assertiveness to great use only when it is in the service of someone else, but not towards one’s own goals or self-interests.

The development of the self also involves the establishment of self-identity, which takes place through experimentation with, and expression of, many facets of the self as these evolve through internalizing the caretakers and other role models. Children “try on” various identifications, including those of other important adults in their life, superheroes and celebrities, peers, and others, throughout childhood and adolescence. The process of identity exploration is nurtured when the parents mirror the transient identifications and self-expressions without scorn, allowing them to occur, accepting a relatively wide range of self-expressions rather than a restrictive one. The message through such acceptance is, it is OK to be you, in all of your transformations, and you are allowed to be all of you and all of your facets and transformations. The healthy outcome of these experiences is a secure and integrated sense of self, in which gradually the child, the adolescent and the young adult has gone through many ‘trial’ identifications and has come to own those parts of them which he or she wants to keep and to leave behind the others that are no longer felt to be part of the essential sense of what is truly “me.” Children of survivors, often overly governed by the need to fulfil parental expectations and to take care of the emotional needs of the parents, might have experienced a limited or narrowed range of options with regards to self-expression, resulting in a sense of foregone options, and aspects of the self that have not been allowed to be included. Moreover, in their relationships, they might feel that the ‘other’ is limiting their expression of themselves, un-seeing, unaccepting or interfering with their ability to be who and what they would like to be. For example, they might feel that the spouse is not supportive, not allowing them to express or develop their true potentials, when in fact, this ‘blaming’ is not based in the current relationship but is due to their own fear of permitting themselves to do what was not allowed for so many years.

Finally, another important group of developmental needs has to do with the sense of competence. The developmental thrust is to become competent, powerful and effective in the mastery of tasks. These mastery needs are nurtured when the parents set developmentally appropriate tasks, ones that are challenging at the right level ( at different ages), and offer appropriate instruction and praise for achievements. The message communicated and perceived with such appropriate challenging and scaffolding of the child’s budding abilities is: you can do it, and I am here to help if needed. The healthy outcome for the child is a sense of personal power, effectiveness and competence. However, trauma-survivor parents might be anxious and over-protective, and thus have difficulties setting appropriately challenging tasks for their children. Paradoxically, while wanting to shelter their children, immigrant trauma-survivor parents might not be able to provide appropriate directions, instructions and assistance when needed by the child, because they are preoccupied with both concrete and emotional difficulties and because they lack the acculturation that would permit them to offer such help to the children, who are functioning in a culture foreign to their parents. As a result, children might grow up having had to be overly, or pre-maturely, self-reliant, which can complicate the capacity to experience and allow closeness in later relationships. Other children might have internalized the parents’ seeming lack of confidence in their ability (which was in reality not that, but the parents’ own fears and worries) and might have subsequently under-developed their own capacities and their own trust in their abilities.

Our relationships with our spouses are opportunities for further personal growth and mutual healing. However, that is not to say that it is the job of our spouse to heal our childhood wounds and compensate for past injuries. Their job, and ours, is to be good partners in the present, with each spouse aiming to become each conscious of their own “baggage.” In conscious relationships, each of us strives to become aware of our own triggers, understand why we respond the way we do, and each attempts to develop a more conscious, intentional way of relating to our partner. As partners who gain a deeper understanding of each other’s relational history, we might try to “stretch” beyond our current defensive character adaptations. We stretch in order to give the other what they need, growing new ‘emotional muscle,’ new emotional ways of relating. The next meeting or two will focus on identifying specific sensitivities, “hot buttons” and automatic responses that are related to characteristics of the second generation and, in particular, on specific strategies to change such automatic responses and to develop more mature and more conscious ways of relating to each other.

Irit Felsen

A very interesting and informative summary. I could really relate to parts of it, especially concerning the difficulties survivor parents had with separation, and also with the effects of emotional unavailability.

I wish there was a discussion meeting held in New Jersey so my sister & I could attend .. I felt a connection & many similarities to many of the points presented & feel a deeper understanding would explain to me “why I am the way I am”. I saw many of my parent’s traits & behavoral patterns in yr discussions .

Dear Sally, it means a great deal to me to hear that the summaries I put on the blog after the meetings of the Discussion Group reach other children of survivors who cannot perhaps attend the meetings, and that these help you understand yourself better! It truly warms my heart to know that, and I am grateful to you for having taken the time to let me know!

I do give presentations in NJ fairly often, so if you sill subscribe to my blog you will see the postings where I post upcoming presentations/events where I speak.

I wish you a very happy, healthy New Year 2017!